Series: The future of arts and culture-driven well-being

“Well-being” refers to a positive state in terms of mind, body, and society.

Under the supervision of Dominique Chen, we present a three-part special edition on arts and culture-driven well-being in the era of life under coronavirus.

2021/01/28

A world we can envisage through the pictorializing of listening

Design researcher

Junko Shimizu

Series: The future of arts and culture-driven well-being

“Well-being” refers to a positive state in terms of mind, body, and society.

Under the supervision of Dominique Chen, we present a three-part special edition on arts and culture-driven well-being in the era of life under coronavirus. Our contributor for part two is design researcher Junko Shimizu.

Questions and concerns that can’t be expressed in words

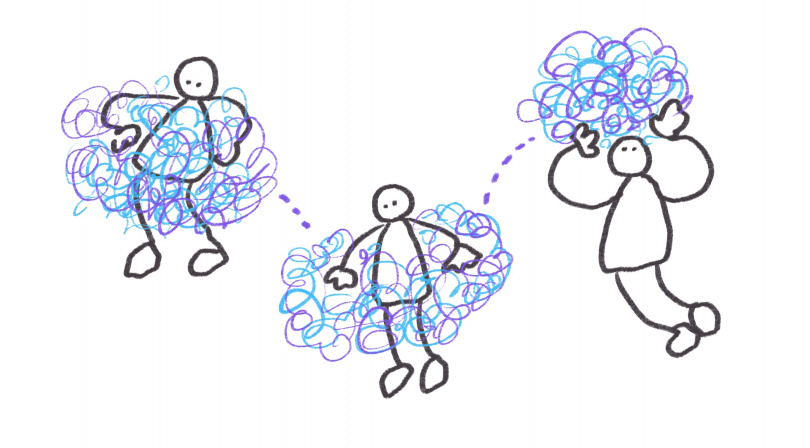

Oftentimes something I can’t put my finger on bugs me all day. In Japanese we call this feeling of not being able to articulate something clearly “moyamoya.” For example, times out drinking when everyone was laughing their heads off, but I couldn’t even raise a smile. Times when ways of spending time I feel comfortable with have not been understood by the family I live alongside. Times when I was talking to someone and realized that what was ordinary for them was special for me. Perhaps I get “moyamoya” feelings when I sense variance between myself and other people. Put simply, moyamoya here refers to questions and concerns etc. that can’t be put into words. It is perhaps also something close to a feeling of discomfort.

Moyamoya flares up from nowhere in the course of a normal day. It rears up with ferocious speed like a tornado, or emerges slowly like a mirage in the desert, and you never know and cannot predict when it’s going to come along. When moyamoya feelings materialize, the world suddenly looks blurred, like when you remove your glasses. Is the sight you are looking at correct? Why is everyone else fine with it? Maybe it’s a hallucination that only you see? You’ll be paralyzed by loneliness. Like the afterimage of a stimulus, a parade of shadows without sound.

What happens to persistent moyamoya?

Sometimes there is some sort of rhythm to moyamoya; it can come on suddenly, and then completely disappears. But sometimes moyamoya becomes something complex and complicated that keeps expanding and seems to swallow your whole body. It’s a headache when this happens. It makes you feel moyamoya towards what should be completely unrelated things. The outline of everything you touch becomes blurred. It’s very uncomfortable spending every day not knowing when the moyamoya you feel will disappear. You feel like you’re wearing wet clothes.

It would be good if I could talk to someone, but for various reasons sometimes I can’t say anything about my lingering moyamoya to the people around me. Even if I were to ask for help from somebody I wouldn’t know, who on earth would I ask? Moyamoya regulation. It’s not business consulting. Nor is it coaching to encourage growth. That isn’t to say I am ready to book myself into a dedicated psychiatric hospital. And I don’t have the time or money to go through the hassle of finding the right counselor for me. I just want someone to listen to me. I want to talk. Where should people go when they feel like that?

An experiment in creating a forum for dialogue on moyamoya

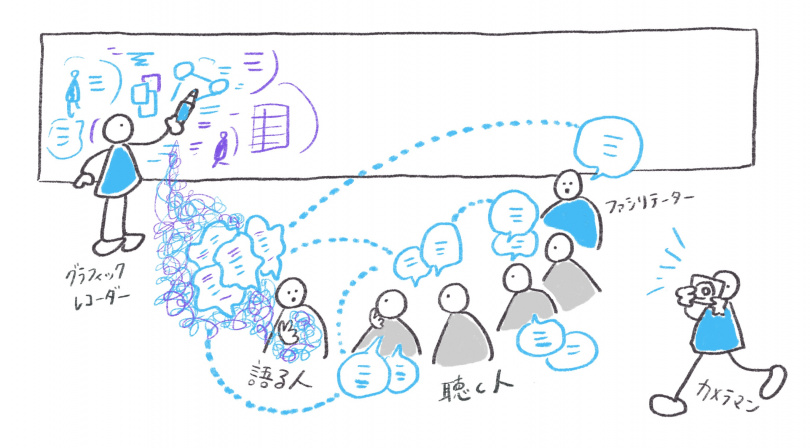

“Moyamoya room” on display in the “traNslatioNs” exhibition directed by Dominique Chen at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT was developed as a response to this question. Moyamoya room is a workshop environment in which participants listen to each other talking about their nagging moyamoya and complex thoughts and feelings. Not only are people listened to, but their feelings are “translated” in real time into concrete form as illustrations. This is an experiment in creating a forum where all participants gather around to engage in dialogue about their graphically rendered moyamoya.

We welcome any participant dealing with moyamoya. For example, people who feel somehow suffocated, cramped, or stuck in their daily lives. People discombobulated by upheavals in their lives such as a job transfer/career change or moving house. Facilitator Yuhei Suzuki encourages participants to share their feelings, which I as the “graphic recorder” then visualize, and everyone gathers around the board to discuss these visualizations. The two-hour or so sessions are being recorded by documentary film maker Asato Sakamoto. Visitors to the museum will ultimately be able to see all stages of the workshop when the resulting video is displayed as a life-size projection on a screen in the “traNslatioNs” exhibition space, with the aim of giving visitors a vicarious experience of the Moyamoya room project. When we started the project we hadn’t worked out the finer points, just the stages in the process.

We went online to recruit participants with moyamoya. Scenes of the participants talking about their moyamoya were going to be displayed in public in an art gallery. It must take a lot of courage for someone to open up about their private moyamoya to people they are meeting for the first time, and for it to be seen by lots of gallery visitors. We were worried about whether we’d be able to gather together people who were willing to talk about their moyamoya, but more people than we expected signed up for the project, and we successfully held seven sessions. As a study of a forum for dialogue, the Moyamoya room experiment yielded many discoveries, but it is too early for analysis and summation. In my writerly guise I’ll set down here some fragments of what I thought and felt.

Moyamoya you can’t express even if you want to, and just hide away

The rising of smoke or steam/ Unclear (objects, causes, etc.) / Lingering feelings of gloom and anxiety. These were the definitions of moyamoya I found in the Shogakukan Daijisen dictionary. But the participants that gathered for project sessions seemed so upfront and upbeat that not one of these definitions was applicable. For this reason, I thought that maybe they were experiencing a mild form of moyamoya which they could talk about with complete strangers, but when the sessions began and Suzuki started questioning them, the words that participants gradually began to share were the very definition of moyamoya.

It might be that other people are not actually able to recognize if somebody is experiencing moyamoya. In fact, I myself stamp out any suggestion of moyamoya in the course of my job and everyday life so that nobody can tell. In my teens and early twenties, I sometimes couldn’t contain my moyamoya feelings, I’d confide in friends and we’d talk things over all night. But everyone has jobs and families when they get older. And people’s values change too. I feel bad when a busy friend makes arrangement after arrangement in order to have a night to themselves for the first time in ages, and we spend the whole time talking about my personal moyamoya problems that have been building up for years. At times like that when I’m getting a late night taxi home from work and haven’t gotten it out of my system yet I feel like saying to the taxi driver, “Um, it’s really nothing to do with the route but I wonder if you’d mind listening for a bit…you see, recently I….” But I feel bad and can’t say anything.

The landscape viewed from illness

On that subject, last year I had an operation for breast cancer. I would like to talk about the moyamoya I experienced at that time. When the treatment started, I was given a questionnaire at the hospital on which was written, “How would you like the doctors, nurses, technicians, and administrative staff to assist and support you during your treatment?” Naturally, I had plenty of questions and concerns about my illness and my body. And on top of that I felt there were a huge number of things I wanted their support with but what I wrote was the three words, “nothing in particular.” It was a lie of course. In fact, there were lots of things. I felt as if I was capable of putting concrete comments in writing like “I’m not good with loud noises,” or “I have an allergy,” but what I felt more strongly at that time was a vague and swamp-like feeling of moyamoya. In that noisy and tense waiting room, it was more impossible for me to draw out my ingrained moyamoya feelings and translate them into sleek sentences than to write an essay in English, something I’m not very good at.

At that moment I remembered myself as a lecturer at university saying, “Please raise your hand if you have any questions!” and myself in business meetings asking, “Does anyone have any opinions?” When I ask other people questions like that, even if I think I am listening to what they have to say in fact I may be incapable of hearing it. Sometimes they are unable to reply depending on their moyamoya. I feel like there are lots of things in life that cause me to ask things in that way without any malice intended. It’s the same situation in this hospital waiting room. No matter how politely I am being asked in writing, I think desperately to myself, “There’s no way I can say what I want to say when it’s asked like this!” And meanwhile I compose a smile under my mask and meekly hand the nurse my questionnaire, on which I’ve written: “nothing in particular.”

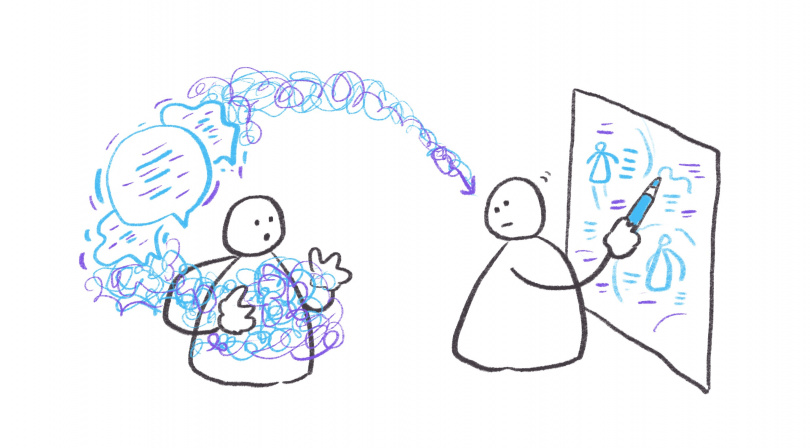

Graphic representation is a signal that your voice has been heard

I went to the examination room when called, with the anxious feeling of a child about to cry rather than that of a grumpy adolescent. But just like the participants in the Moyamoya room project, I go into the room in a bright and breezy manner showing no sign of what I am feeling. I listen to my physician’s explanation of what is going to happen from now on. He explains what sort of operation they will perform as he draws a beautiful diagram with a practiced hand on a sheet of A4 paper. I tried to communicate to the physician in a no-nonsense way the moyamoya I had been feeling before and couldn’t find the strength to translate into words. But again, for some reason the words I resolutely began to say ended up disintegrating into incoherence at the end. The physician listened with calm and composure, interpreted the meaning of what I wanted to say from my voice, and put it down on paper in clumsy and unpracticed lines that differed from the previous drawing. It undoubtedly represented my words, in my voice. In that moment I was enveloped by a great feeling of reassurance.

I felt as if the outline of the moyamoya inside of me had become vaguely visible.

It was then that for the first time, I felt I understood the significance of the “graphic recording” I did in the Moyamoya room project. The finished “graphic record” seems like a means for me to visualize the moyamoya of participants. But actually the “graphic record” is the visualization of what I as “graphic recorder” hear. In other words, “graphic recording” functions as a device for participants to see the extent to which their voice has been heard in the way they wanted it to be.

By experiencing at a very unstable moment in my life the perspective of the person whose feelings I am pictorializing, I realized that there is profound meaning and possibility in graphically representing a person’s voice there and then in real time. Something more fundamental and important than the “easy to understand, easy to communicate” theory that always comes up when you apply Gestalt Principles (the cognitive tendency of people to perceive things as a whole). The proof that the other person has heard your voice. The genuine feeling that your voice has gotten through to the other person. A pen that moves every time you speak or stops for your silence is like a boat that moves in the wind. The desire for the pen to keep going gives you the strength to vocalize in a way that seems to get to the heart of your moyamoya feelings.

A space that expands through the pictorializing of listening

What people with uncontainable moyamoya are looking for is not a freeform questionnaire with limitless scope for writing on. Neither is it a question of passively catching and listening to sound with your ears. They want people to have a feel for their moyamoya and to listen with undivided attention in an effort to understand the background and the feelings. What’s more, if possible after that they want you to gradually and solemnly ask questions back such as “Why did you think that?” or “What does that mean?” in order to draw out their true voice even further. They want you to listen, not just ask. And they want you to enquire. I’m not talking about the biological function of hearing but the profound power of hearing/listening/inquring that human beings can bring to bear with their whole body.

“This exhibition is a record and a vicarious experience of time and space in which we took a straightforward look at moyamoya. As you look at this exhibition, I’m sure that the moyamoya inside you will raise its voice. What sort of voice is it? Herein lies the meaning of this exhibition.” This is the statement I wrote when the exhibition started. What does your moyamoya look like now as you read these lines?

Is the internet over-connecting our voices?

The coronavirus pandemic continues in 2021. In an era when the future is uncertain, people all over the world will feel moyamoya such as they have never experienced in the past. As the distance between people increases, many people are casting their own moyamoya in the direction of the whole world using the social media at their fingertips, in an effort to have even a modest collective emotional experience. In addition, there could well be a lot of people who sort out their feelings by being on the receiving end of this moyamoya. In an era when we can’t get close to each other and exchange our real voices with each other, the internet has become our voice instead, racing around around the world and connecting us.

Over the last 1,000 years mankind has managed to develop and secure a variety of platforms designed to amplify the voices we produce. Printing, photography, radio, the telephone, television … and now the internet. Even if people can’t meet in person, their voices can no longer be blocked. The world resounds with our shared voices through a variety of channels. The internet in particular is a powerful adhesive that connects all our feelings equally. However, on the flip side of that, I see it as having something extreme about its nature due to its power, as something that connects all kinds of emotions yet never connects different kinds of information.

The internet takes any shape to connect our feelings, but that shape cannot necessarily be connected to other thoughts and feelings. It’s like building a castle with the two different materials like Lego and bamboo sticks. Individual materials connect well together but it puts considerable stress on things when different materials overlap. When you put Lego together the parts are all alike. But when it comes to adding bamboo sticks to the mix, a completely different approached is required. It’s the same if you look at it from the perspective of the bamboo sticks. Without being woven together as usual, the bamboo sticks may damage the surface of the Lego.

Pointers lying dormant in the oldest forms of communication

In moments of variance like these on the internet, somebody’s moyamoya can get tangled up with your own and get bigger, filling our hearts and minds. The power of all platforms of communication, imbued with 1000 years of human wisdom, is lost, and the landscape of the heart gradually erodes into darkness. What can we do at such a time? Is there no choice but to grin and bear it?

So I have a proposal. Hear, listen to, ask about the voice of those close to you. And if you can, try using a pen when you do. Just a little, try slowly turning the words of the person you have listened to into a drawing. We can’t travel far these days so let’s take a trip that can be made with just the pen and paper on the desk. Let’s venture out into a world we can envisage through the pictorializing of listening.

Voices, which existed tens of thousands of years before today’s array of technology developed. Pictures etched in caves. You might call these the oldest media environments in our long history. The starting point of the new possibilities I felt in the Moyamoya room project may have already existed in landscapes like these. If you feel constrained by and tired of today’s information environment, leave the Internet for a while, talk to the person in front of you, and give their voice your undivided attention. Immersing yourself in this simple experience may provide some valuable pointers.

Related Article

Series: The future of arts and culture-driven well-being

- A dystopian future and well-being

Ai Hasegawa (Artist) - The future of arts and culture-driven well-being

Dominique Chen (Associate Professor at Waseda University, School of Culture, Media and Society since 2017)