Series: Arts on the Globe: Challenges and Prospects under the COVID-19 pandemic

In this series we report on how arts and culture have faced up to the challenges of coronavirus in Europe, North America and neighboring countries.

2021/12/21

CASE05

The Outlook for Japan through the lens of Germany’s pandemic-related cultural policy (Part 1)

Associate Professor, Dokkyo University

Yuki Akino

Series: Arts on the Globe

In this series we report on how arts and culture have faced up to the challenges of coronavirus in Europe, North America and neighboring countries

The pandemic’s impact

“From material wealth to wealth of the heart and mind.” This tired formula is repeated automatically when the evolution of Japan’s postwar cultural administration is discussed in a historical context *1. We became aware of this disturbing “magic spell” during the pandemic that has thrown the world into an unprecedented crisis. In February 2020, when it became apparent that the novel coronavirus was starting to spread in Japan, the government called for “self-restraint” in cultural and entertainment activities. This development sent major shock waves through the cultural community, where it was interpreted to mean that the field had been given the blanket designation “non-essential and non-urgent.”

But can this be wholly attributed to the problem of politicians who are said to have no understanding of culture? “After Japan became economically wealthy, the next step was to focus on promoting the arts and culture”… Who prepared the ground for this “step by step” narrative to be collectively internalized by the Japanese people and for culture to be perceived as something “extra” that can only be enjoyed by well-off societies and as a matter of individual taste? It seems to me that it was the people in my profession—cultural policy researchers.

At the core of cultural policies implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic is emergency assistance—creating a distinction between current objectives and those in ordinary times. But the pandemic has become an opportunity to reconsider what culture means to society, whether in normal times or times of emergency. Cultural Businesses requesting support and continuation of their activities; public opinion dividing into poles of criticism, support, and neutral observation—the newly revealed fragility of the casual assumption that we had all agreed on the meaning of the arts and culture… Some of the premises that formed the foundation of pre-Covid cultural policies have quietly collapsed.

The Grütters whirlwind arrives in Japan

After jeers were directed at phrases uttered by Japanese politicians, the “Grütters whirlwind” arrived from Germany, and this in turn was elevated to an excessive degree. Monika Grütters, who was then in charge of culture and media-related matters in the German government, was suddenly showered with praise in Japan. (BKM, the German abbreviation of her official title, will be used hereafter in this article.) The “culture minister of Germany” (2) was said to have called artists a “life support apparatus,” promised “unlimited” support for freelance artists, and described culture as “fundamental to democracy.”

The original German phrase that was translated into Japanese as “life support apparatus” was actually a predicative use of the adjective lebenswichtig (“vitally important”), rather than a special phrase with a nuance evoking medical equipment. As for “unlimited support,” the German government’s watchword at that time was that it was prepared to do what was needed, “whatever the cost.” The hook may have been the word “unlimited”; in any case, until June of 2020 the media and even members of Japan’s parliament repeatedly exclaimed that “Germany is going to give freelance artists six trillion yen.” Actually, this was the total amount of the German version of “sustainability benefits” provided to individual business owners and small and medium-size businesses overall.

Nonetheless, the information reported in an exaggerated way did serve to plant a seed in Japan at the time, drawing attention to Germany’s cultural policies and paving the way for a wide-ranging debate on economic assistance in Japan. Taking this background into account, Part 1 of this article will outline ways in which culture has been supported in Germany during the pandemic. Part 2 will consider the meaning of the “big noise” around German cultural policies as viewed in Japan.

The Berlin (top) and Bonn offices of the BKM, which has spearheaded the German government’s cultural assistance programs during the pandemic. (Photos: Yuki Akino)

Agencies in Germany’s central government are divided between Bonn and Berlin. With an additional BKM office in the Chancellery in Berlin, the German federal government has a total of three cultural policy bases.

Trends in Germany

1) The balance between principle and practice required in a time of crisis

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 a pandemic. On that day in Germany, where a pandemic warning had already been issued on March 4, (then) Chancellor Merkel and the country’s health minister explained the cancellation, which had been decided at the previous day’s cabinet meeting, of events of over 1,000 people. *3

In normal times the promotion of culture in Germany falls under the states’ jurisdiction. At that time, however, the German federal government and state governments agreed to establish uniform nationwide regulations in order to contain the spread of infection. Cultural activities could not be left out of this plan. Therefore, Grütters explained on behalf of the German government the need for restrictions regarding the cultural/creative sector, and promised governmental support. (At that time, however, organizers of small-scale events that had not received government assistance were permitted to decide independently whether to hold the events.)

“This situation will place a large burden on the cultural/creative sector. We are aware that comparatively small facilities and freelance artists are likely to experience hardship.”

“Culture is not a luxury item to be enjoyed only in good times.”

“The reason we are nonetheless calling for the cancellation of events is that we are in a highly unusual state of emergency.” *4

Grütters expressed a great deal of sympathy concerning the disappointment of industries whose activities would have to be canceled. At the same time she stated that, as the government was calling for restrictions, she would speak within the government on behalf of the cultural/creative sector and explain its unique circumstances, and make sure they were reflected in subsequent assistance. Her remarks were both an explanation of the current situation and an expression of determination regarding forthcoming measures. Grütters explained that restrictions on activities did not mean the industry’s importance was being taken lightly—and this speech, along with the assistance amount that followed, drew the attention of people in Japan.

On March 22 it was announced that gatherings of three or more people (other than family members in the same household) would be prohibited throughout Germany for an initial period of two weeks. ※5 This was effectively a city lockdown. ※6 On the 23rd, the German government announced a program of additional large-scale measures that it called “comprehensive emergency support in response to the coronavirus.” This series of vigorous, sweeping assistance measures, announced step by step since early March, was nicknamed the “bazooka.”

※6:On the 18th, a few days before that announcement, Merkel had explained to the nation that such a decision cannot be made lightly in a democratic society and these were just temporary measures, and that (as a native of the former East Germany) she was keenly aware that freedom of travel and movement were hard-won rights; but that these difficult decisions had been made in order to save lives. Actually, in the interim period Merkel called for self-restraint concerning “participation in non-essential events”—that is, she used the same phrase that Japan’s politicians have used—but it was clear from the context that this was an across-the-board request (applied even to family gatherings) to maintain physical distance between people. This is why the government was not inundated with critical comments such as “Why is it all right to do this but not that?” The restrictions were subsequently extended. Starting on April 20, some activities were permitted to restart on the basis of floor area.

Initially there was a positive response to the fact that subsidies made available to individual business owners and small businesses (from a revised budget of 122.5 billion euros) were not loans, but payouts. (Fifty billion euros is equivalent to six trillion yen; below, one euro equals 120 yen for the first half of 2020, and the assistance amount for 2021 is calculated at the rate of 130 yen to the euro.) This is because most culture-related businesses, including for-profit enterprises, were supported by entities with relatively fragile business foundations, and many in the field commented at the time that a loan, which must be repaid, “would be nothing but a postponement of our demise.”

This immediate assistance was provided in a lump-sum payment of the compensation amount for three months. While speaking in various media about the social significance of culture sphere, starting on the 20th Grütters gave advance notice of assistance from the “bazooka” that would be available to those engaged in the cultural/creative sector. As a result, a misunderstanding arose in Japan: that is, the measure to be implemented on the 23rd was thought to be an assistance amount earmarked for culture only. The statement that “Germany is going to give six trillion yen to freelance artists” continued to be repeated in the Japanese parliament and the media until June. ※7。

Grütters concluded the assistance-related press release of the 23rd as follows:

“The imaginative courage of creative people will surely help us overcome this crisis. From this crisis we must seize every opportunity to create good things that will benefit the future. Therefore, at this moment in time, artists are not only essential, they are vitally important.” ※8。

These concluding remarks were grouped together with “six trillion yen in assistance to freelance artists” and “life support apparatus” (the creative transformation of “vitally important”) and instantly disseminated on SNS in Japan, garnering plaudits. ※9 Even now, the statements of German politicians are quoted repeatedly in the context of cultural assistance in various countries during the pandemic.

Despite inaccuracies in nuance at the time of translation, the overall message was definitely heard in Japan. The fact that various phrases used by German politicians were met with both admiration and a certain astonishment was unquestionably related to differences in perspective—that is, societal perceptions of culture—in Japan and Germany. As I will discuss in Part 2, surface issues like monetary amounts and speed of response are not the only aspects of this phenomenon that should be examined. Beyond these are differences between the two countries’ understanding of why cultural policies exist, which connects to the background issue of the relationship between society and culture. The statements of politicians in Germany are not an overnight phenomenon.

2) Pandemic assistance for the cultural/creative sector

Policy concepts will be left for Part 2. In Part 1, I will first focus on practical policy matters likely to be of great interest to arts managers and administrators, and attempt to capture a complete picture of this assistance.

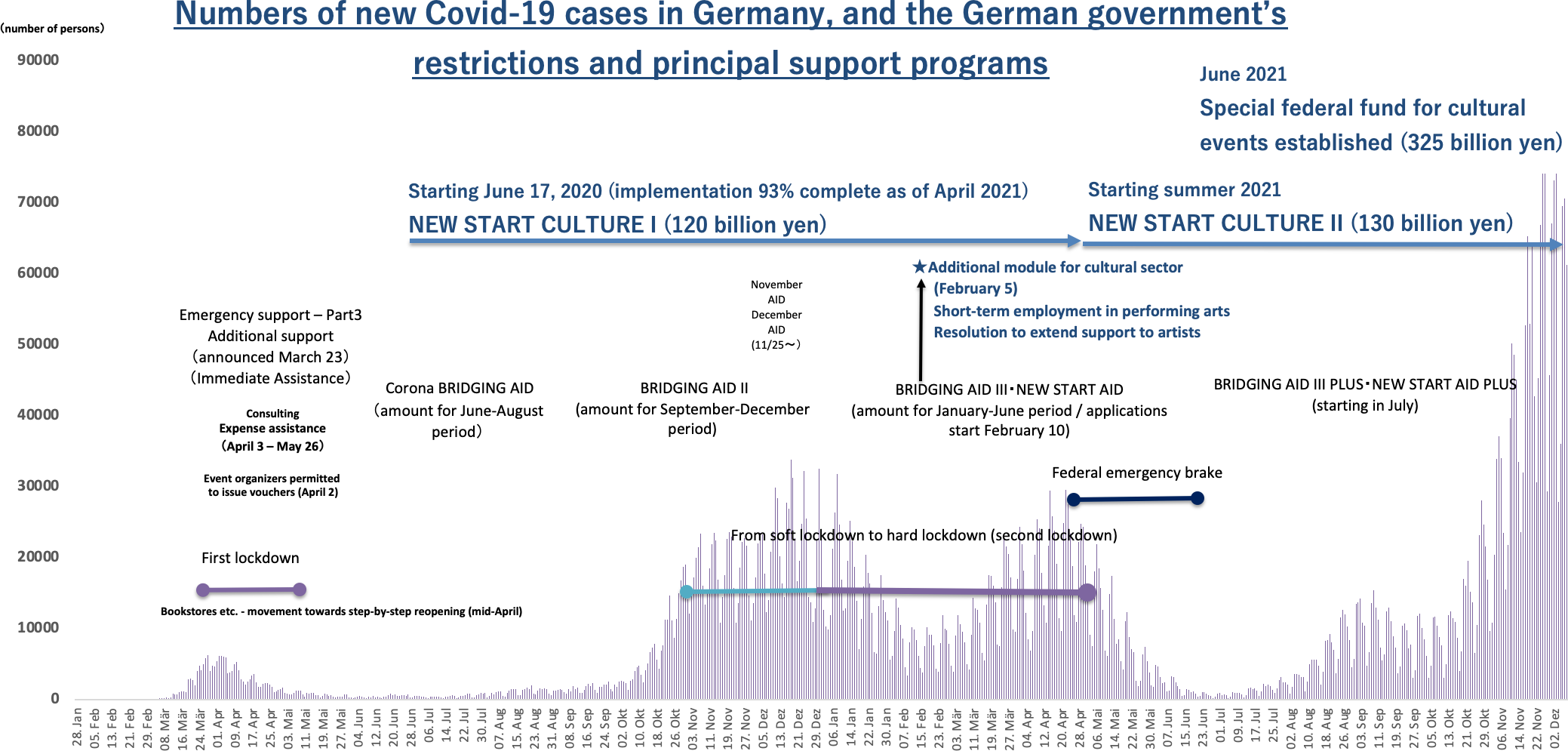

In Figure 1, I have shown the principal assistance measures introduced by the German government up to July 2021, along with the state of Covid-19 transmission and accompanying restrictions. The parts in blue are support programs exclusively for the cultural/creative sector. Other parts are the German government’s support programs for industry, including the cultural/creative sector. Figure 2 shows the support provided by state governments in the early part of the pandemic (as of April 8, 2020). Incidentally, Germany’s cultural/creative sector includes 136 industry types, and is defined more broadly than in Japan’s national census. *10。

In making comparisons between the budgets of various countries, definitions and industry scale must be taken into account. In Germany there are 1.3 million core workers employed in the cultural/creative sector, the highest number of any European nation (Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology, Germany: Monitoringbericht Kultur und Kreativwirtschaft 2020 [Kurzfassung]). There were 410,000 “artists” in Japan’s national census as of the end of March 2020, which was cited when the second revised budget was formed in June 2020. (In the Agency for Cultural Affairs “Culture and arts activity continuation support program” of FY 2020, about 80,000 subsidies were granted, or about 83% of the total number of applications.) Initially in Japan, there was debate as to whether music clubs would be included in the cultural assistance program, but Grütters declared early on that this assistance took clubs into account.

Figure 1: Numbers of new Covid-19 cases in Germany, and the German government’s restrictions and principal support programs

(Large size:PNG/PDF)

Information on infection case numbers is from the Statista Excel data Täglich gemeldete Neuinfektionen und Todesfälle mit dem Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Deutschland seit Januar 2020 (up to December 10, 2021), based on data from the Robert Koch Institute. This chart was prepared by Yuki Akino, referring to the following sources: Information on lockdowns and other restrictions refers to data released on the German government website and a related article in Wirtschaftswoche. Information on national-level emergency support other than cultural support refers to data released by the German government and JETRO (Dusseldorf, Berlin, and Munich offices).

Federal emergency brake: If the number of new infections exceeds 100 new cases per 100,000 persons in the past 7 days (7-day Covid-19 index), strict (near-lockdown level) restrictions are implemented on a per-city/per-district basis.

* These measures apply to people for whom creative work comprises at least half of their annual income. Various measures have been implemented, including expansion of the tax exemption framework to about 360,000 yen for teaching artists/part-time artists.

Figure 2: State government support in the initial phase of the coronavirus pandemic (as of April 8, 2020)

| State | Whether or not state support is linked to German government support |

Whether income reduction/loss is a condition for receiving payment |

freelancers/individual business owners |

Small businesses (up to 5 full-time employee posts) |

Small businesses (up to 10 posts) |

Small and medium-sized enterprises (up to 15 posts) |

Small and medium-sized enterprises (up to 24 posts) |

Small and medium-sized enterprises (up to 25 posts) |

Small and medium-sized enterprises (up to 30 posts) |

Small and medium-sized enterprises (up to 49 posts) |

Small and medium-sized enterprises (up to 50 posts) |

Small and medium-sized enterprises (up to 100 posts) |

Small and medium-sized enterprises (up to 250 posts) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Wurttemburg | Now voting | 〇 | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 30,000€ | × | × | ||||||

| Bavaria | Reconciliation | × | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 30,000€ | 50,000€ | |||||||

| Berlin | Additional support adopted | × | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 25,000 euros (from Berlin’s independent fund of 75 million euros) | × | |||||||

| Brandenburg | Reconciliation | × | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 30,000€ | 60,000€ | × | ||||||

| Bremen | Additional support adopted | 〇(2,000€) | 2,000€(※i) | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 20,000€ | × | × | × | ||||

| Hamburg | Additional support adopted | 〇 (for individual business owners) |

2,500€ | 5,000€ | 5,000€ | 25,000€ | 30,000€ | ||||||

| Hesse | Special rules | × | 10,000€ | 20,000€ | 30,000€ | × | × | ||||||

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | Additional support adopted | × | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 25,000€ | 40,000€ | 60,000€ | × | |||||

| Lower Saxony | × | × | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 15,000€ | 25,000€ | × | × | × | ||||

| North Rhine-Westphalia | Reconciliation | 〇(2000€) | 2000€(※i) | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 25,000€ | × | × | |||||

| Rhineland-Palatinate | × | × | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 30,000€ | × | × | × | × | ||||

| Saarland | × | × | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

| Saxony | × | × | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

| Saxony-Anhalt | Reconciliation | 〇(400€) | 400€(※i) | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 20,000€ | 25,000€ | × | × | ||||

| Schleswig-Holstein | × | × | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

| Thuringia | × | × | 9,000€ | 15,000€ | 20,000€ | 30,000€ | × | × | |||||

※:For enterprises in , German government programs are applied. The German government’s “bazooka” (support program) was applied only to enterprises in (small businesses up to 10 posts).

※:In “numbers of posts” indicated here, one post is a full-time position. The number of employees comprising one full-time post varies according employees’ working hours. The actual numbers of employees and posts are not always the same; for example, one full-time post may be filled by two part-time workers. The conversion method for the number of employees is as follows: up to 20 working hours = 0.5 employees; up to 30 working hours = 0.75 employees; salaried employees working up to 30 hours and trainees = 1.0 employees; workers with a base wage of 450 euros = 0.3 employees.

Sources: This information refers to the Federal Government’s Centre of Excellence for the Cultural and Creative Industries, “Table of state support during the Covid-19 pandemic” (received by e-mail on April 10, 2020), pp. 12-13; regarding Berlin, the resolution of April 9 was appended. The conversion method for post numbers is based on the definition specified by Germany’s reconstruction and development bank (KfW).

2)-1 Government assistance in Germany

The German government initially put together an assistance program for individual business owners, small businesses and freelancers, and announced that previously adopted assistance would be spent in a flexible way. It subsequently shifted its focus to “New Start Culture I,” a program to assist public cultural facilities and organizations.

At first, a three-month suspension of activity from March to May (first lockdown) was envisaged. About 80,000 events were canceled throughout the country, and the preliminary estimate of financial losses in the cultural/creative sector was 1.25 billion euros. ※11

Public cultural facilities were attended to later because they are operated with an annual budget and it was therefore thought that a few months’ closure would not directly cause them financial hardship. But here I must touch upon aspects of Germany’s assistance program in this period that were not often mentioned in Japan.

First, there is the long-standing issue of the disparity in funding within the field of arts and culture, a “weak point” specific to Germany’s cultural policy. In Germany, the “generous” nature of systematic support for public theaters and the like, and the much more tenuous support for the “free scene” consisting mainly of freelancers, are two sides of the same coin. (Statistics even show that in Germany, where support for performing arts comes mainly from state and local governments, the official per-seat performance subsidy amount is just over 10,000 yen for the former, but just under 100 yen for the latter.) *12 In the past few decades, cultural policy has come under fire for failing to rectify this disparity. Amid this pressure for structural reform of the environment for creators, and faced with an unprecedented pandemic, it was inconceivable—even setting aside the fact that a federal election was coming up—that the German government would not support artists on the free scene, or that it would implement measures that appeared to take these artists less seriously than systematized cultural institutions.

The second point is that, while both a statistical grasp of industry “scale” and an understanding of various individual “work styles” were required in implementing emergency assistance, Germany showed strength in the former but fell behind in the latter. There was much interest in how the presence of the cultural/creative sector would be given recognition, and how the industry’s unique circumstances would be reflected, in the implementation of the “bazooka,” which was the German government’s initial action in providing emergency support for the cultural/creative sector. This proceeded in a relatively logical and precise manner, supported by the customary processes of “understanding the situation” and “monitoring.” Germany’s Federal Employment Agency compiled statistics on numbers of employees, industry scale, income structure and so on in the cultural/creative sector. The political discussion process leading up to the launch of the “bazooka” emphasized the “scale” of the cultural/creative sector; and, while in normal times the federal government is involved in the arts and culture only in limited situations, this information facilitated the incorporation of wide-ranging assistance for creative workers (including those in the arts and culture) in the German government’s immediate assistance program.

In regard to statistical data compiled by Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy (then, today: the Federal Ministry for Economic and Climate Action), which administers the cultural/creative sector in the framework of industry support, creates cluster maps for each industry showing shifts in real numbers, growth rates and industrial structure, as well as their nationwide distribution, and releases the maps as part of the cultural/creative sector monitoring process. In Germany, the cultural/creative sector has the third-highest gross value added (GVA) after the automobile and machine manufacturing industries, accounting for 3% of GDP. At universities in Germany, these statistics are taught in the first lesson of cultural policy courses. *13

The success or failure of a policy plan depends on whether it starts with an accurate and detailed understanding of the current situation. In this case as well, that basic foundation had been thoroughly prepared. Everyone from the BKM, lobbying groups, the media and artists to those of us in the research field was able to discuss and consider the general outlines of an ideal support structure for the cultural/creative sector, even in the period before the “bazooka” was implemented, based on the multifaceted statistical information that is released.

But even though a succession of assistance programs was launched when restrictions were subsequently put into place (as shown in Figure 1), it is difficult to give an unreservedly optimistic assessment as to whether these programs were easily usable by all freelancers who are engaged in creative fields and have diverse working styles.

This support, which was cited in Japan as ideal, actually focused on businesses that have fixed expenses like rental and fuel costs—galleries, bookstores, small movie theaters, music clubs and the like. It’s true that the “individual business owners” who were eligible for support could be called freelancers, but freelancers’ working styles are diverse. I am not an expert on German labor law, so my understanding is based on typical discourse in the field rather than legally precise classifications; but broadly speaking, two types of freelancers come to mind: 1) actors, singers or dancers with their own office, practice studio or atelier; and freelance managers of bookstores, small movie theaters, and clubs (self-employed individual business owners/Solo-Selbstständige); and 2) freelancers whose work involves providing their own skills in the creation of multiple artistic works in various settings (Freischaffende, freie Künstlerinnen). It seems that quite a few people in Japan had mainly the latter category of freelancers in mind when they heard about this assistance, and held a favorable view of the German government’s response at the time. However, this system was actually designed mainly for those in the first category. *14

For this reason, Grütters was harshly criticized as early as April of 2020. In a program broadcast on the station ARD on April 17, she made the following remark in reference to freelance creative workers in the second category above, who do not have fixed expenses: “I would like to ask them to make do with the social security package, which can also be used for living expenses.” Although a substantial portion of those who effectively support the cultural/creative sector are in the second category, she explained that they also had the option of using the unemployment allowance. *15 The main purpose of emergency assistance was actually industry protection, which prioritized avoiding bankruptcy among businesspeople who had practiced sound management and preventing acquisition of businesses with overseas funds. Thus, at that juncture problems remained in the German government’s response, which had not been perfected to the point of being a universal and complete support structure encompassing all individuals who worked in the cultural/creative sector and truly needed help.

For some time Grütters bore the brunt of criticism of the government, which increased and became more intense by the day. In mid-April there were indications that bookstores and museums would reopen; but theaters, concert halls and the like remained closed. At the end of April, it was confirmed that compensation for canceled fees would be paid from the BKM budget (though this was limited to artists who had contracts with facilities and projects receiving government subsidies); and event organizers were able to mitigate (delay) the impact of reimbursement for canceled concerts by issuing vouchers for future use. On the other hand, there was little change in the situation of freelancers, particularly those in the performing arts field. Finally, on May 9, instead of the much-criticized Grütters, it was Merkel who appeared. As many know, it was favorably reported in Japan that the chancellor had called support for the arts “the highest priority” *16; but the most important point was that she consciously referred at the outset to the fact that artists, especially freelancers (die Freischaffenden), had been particularly hard hit. *17

*17: Video-Podcast “Merkel sichert Kulturschaffenden Unterstützung zu”

Merkel concluded by saying the government’s aim was for “Germany’s wide-ranging and richly diverse cultural landscape to continue to endure” after overcoming the disruptions caused by the pandemic, and that this challenge was at the top of the German government’s list of priorities. The freelance artists who were fuming with anger over their inability to work and the inadequacy of assistance may have been thinking, “The only thing that isn’t in place yet is assistance that reaches us, so of course it’s the top priority!”

At the beginning of June, a support program designed specifically for the cultural sector was finally announced. Called “New Start Culture,” it supported the establishment of infrastructure (online ticket sales, digital projects with the possibility of with the possibility of charging fees, air conditioning/ventilation provisions, etc.) so that private cultural facilities, and facilities whose operational expenses are not, for the most part, covered by public assistance, could reopen and implement infection control measures. It also aimed to provide facility and project assistance for small and medium sized private business operators, and thus disseminate support for freelancers and individual business owners through the creation of new jobs. In regard to cultural institutions and projects subsidized by the German government, and public cultural institutions/projects run by state and local governments, it attempted to compensate for income lost due to cancellations, as well as additional expenses resulting from the pandemic. While applications were submitted by groups, the program’s goal of ensuring that assistance reached freelance artists was emphasized repeatedly from the start.

Since then, there has been a continuous rollout of government support for which individual business owners and small businesses can apply. Indeed, the German government had statistically grasped the importance of freelance creative workers in the cultural/creative sector, and to some extent had gained an accurate understanding concerning people enrolled in social insurance for artists and members of industry-specific associations such as those under the umbrella of the German Cultural Council. But in terms of its grasp of the true scope of these groups’ specific work processes, which is extremely important in providing them with emergency assistance, it seems the German government, like the Japanese government, continued to struggle.

In a lecture she gave at Kobe University on December 9, 2021, Annegret Bergmann, project associate professor at the University of Tokyo, pointed out a problem that exists in Germany: the fact that singers, musicians, actors, and technicians—who have a more fragile foundation for their livelihood than any other type of freelancer, since they simultaneously work under multiple temporary contracts for individual creative productions—had been left behind by all assistance frameworks. Professor Bergmann said the work of most of these people is regarded as full-time employment when multiple contract periods for various productions exceed six months, and at that point they become ineligible to apply for assistance for self-employed workers. In fact, they are not full-time workers either, and therefore cannot receive subsidies in that framework (i.e., short-term labor benefits). Thus, they seem to have slipped through all the gaps in assistance for over a year, until the implementation of the additional 2021 module (see Figure 1).

Bridging Aid III, for which applications began on February 10, 2021, was initially an assistance program in which individual business owners and people engaged in non-regular employment could apply for a maximum of about 975,000 yen from January to June 2021. Just before the application period, however, an additional module for the cultural sector was announced and eligibility was expanded to include “artists in short-term employment in the performing arts field.” *18 It was explained that, because they can only work for a limited time in guest appearances or films, these people had previously been ineligible to apply for either unemployment allowances or short-term labor benefits.

https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Pressemitteilungen/Finanzpolitik/2021/02/2021-02-05-beschaeftigte-darstellende-kuenste-neustarthilfe.html

Bridging Aid III also included New Start AID, a program for individual business owners who were previously unable to benefit from assistance for fixed expenses. With this program they could receive a one-time payment of 25% of their 2019 sales earnings (with an upper limit of 5,000 euros). *19 In New Start AID PLUS, which began in July 2021, it was stated in writing that the program “includes non-regular and short-term employees in the performing arts.” The amounts have since been increased; currently (2021 December), individuals can apply for a maximum of 580,000 yen, and enterprises and cooperatives with multiple employees can apply for a maximum of 2.34 million yen. There is a great disparity between being eligible and being ineligible for this bridging assistance. (However, all Bridging Aid programs include a condition that the percentage decreases if the income exceeds a certain amount.) In ordinary times, the German government’s support for this field is slight (as the field is not under federal government jurisdiction). Therefore, while it is true that there was a delay in grasping the industry’s circumstances, it did turn out that a segment of freelancers had to wait until then to receive the pandemic emergency assistance that was touted by the federal government as “prompt and non-bureaucratic.”

2)-2 State-run assistance: multilayered support through allocation and cooperation

As of April 2020, German government support ,which was receiving attention in Japan, was as indicated in of Figure 2. From this we see that, while the “bazooka” did offer help to the cultural/creative sector, in reality the support was only for individual business owners and small businesses with a maximum of 10 employee posts.

As of 2019, business operators in Germany’s cultural/creative sector had 4.66 employee posts on average, and individual business owners made up 20% of the industry’s labor market. *20 Thus, even with eligibility limited to businesses with 10 employee posts or less, the majority of businesses could be covered. On the other hand, larger businesses do exist.

This is where state governments came in. *21 Germany has a federal system, and cultural legislation in particular is under the “sovereign authority” of the states. Quite a few states had drafted their own budgets and begun support programs in advance of the German government. As shown in Figure 2, states nationwide added their own support programs to payments from the federal government, and accepted and responded to applications. This “decentralized implementation system” effectively dispersed and lightened the administrative burden on the German government. Regional discretion also enabled the programs to reflect each area’s specific circumstances. *22

*22: In April 2020, Klaus Lederer of the Left Party, Deputy Mayor of Berlin and Senator for Culture and Europe of Berlin, participated in an online lecture held by the Goethe-Institut Tokyo. Listening carefully to his remarks, one notices that he emphasizes not the excellence of “Germany’s” response, but the slowness of the federal government’s (CDU/CSU and SPD) response and the speed of Berlin’s own assistance program.

The German government stated that payments should be targeted to the continuation of business and set aside for atelier and studio rental fees rather than living expenses. But there are many creative workers, especially in the performing arts, whose activities do not fit this condition.

On April 17, the aforementioned newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung stated its view that only the states of Hamburg, Berlin, and North Rhine-Westphalia had narrowly succeeded in providing “prompt assistance.” The reason was that these states had made it possible for people to quickly apply for assistance if they had submitted their work address to the tax office, even if they worked at home and had no other workplace.

In another example, the state of Baden-Württemberg independently established a sort of individual basic income (about 140,000 yen). In applications for “immediate support,” writing down specific items necessitating financing (lease, rent, credit, etc.) was required. At that time the state made it possible to effectively guarantee individual basic income by allowing for the appropriation of up to 1,180 euros per month in the form of provisional employer payment (remuneration) to individual business owners and self-employed people. In other words, in states that made these adjustments, support programs provided the assistance for actual living expenses that was sought by creative workers who had lost jobs due to pandemic restrictions, rather than compensation for fixed expenses. Additionally, Baden-Württemberg later established (indefinite-term) digital employment positions in state-run museums, and hired 23 workers. The state continued to implement measures not just to support artists, but also to provide residents with digital programs.

The state of Schleswig-Holstein established the incentive assistance program “3×3” for film industry producers, screenwriters, and directors, with the aim of encouraging the production of new works in the long term. The program was created with the idea of “three new scripts in three years,” and as no one knew how long the pandemic would continue, it did not press for quick results as if this was a condition for receiving assistance. Various subsidies supporting rehearsals and the like have also been created. The states’ diverse support initiatives encompassed many unique ideas and solutions because they had long observed up close the working methods of people in creative fields and worked in cooperation with local cultural associations.

(2)-3 The main actor in civil society—the “arm’s length body” implementing execution and planning

Federal government support specific to the cultural field took shape in June of 2020. *23 The aforementioned New Start Culture I was organized as a group application/group distribution program. Though assistance was received by groups, there was a condition that it would reach freelance artists. Maintaining quality was also taken into account. The program supported various types of activity including movie theaters, museums, theaters, music, and literature, and included the development of digitization and investment in pandemic response (hygiene-related equipment, air conditioning/ventilation provision, etc.).

Here I will briefly describe industry-specific “councils,” the main entities receiving applications and conducting examinations. The “arm’s length body,” which is positioned as a breakwater for direct intervention by the government, is an entity that is also emphasized in the area of cultural assistance as long as expertise and fairness are maintained. Conceptually, it is regarded as a highly specialized entity that independently judges programs’ cultural quality and public significance, with no government intervention. Germany’s arm’s length bodies are multi-tiered, with industry, area, and quasi-governmental types. It was the industry type that proved important in the group support system. *24 Currently there are eight industry-specific councils, unified under the umbrella of the German Cultural Council.

For example, in the German government’s New Start Culture I, the application process and selection of cultural groups related to the social/cultural field was implemented by the “social/cultural council,” an industry council. The German Cultural Council carries out continuous lobbying activities broadly promoting the public nature of culture throughout society. Cultural associations and foundations have also made efforts in the area of selection and allocation. Moreover, through these organizations, the German government makes a point of gaining a thorough understanding of the constantly changing situation, and the Cultural Council’s managing director is invited to nearly all German government meetings (committee meetings are live-streamed online). On a daily basis the council sends out and publicly releases a newsletter with requested support design plans and amounts, progress reports, and fundamental statistical materials. While carrying out this division of roles, each council connects various actors and entities at different levels of government, and presents to the government specific examples of problematic situations and designs for needed measures. Most such measures were eventually adopted in the German government’s pandemic assistance programm. (In the first half of 2021, the Cultural Council issued the three-centimeter-thick book “Corona Chronicles I,” documenting and compiling support at each governmental level as well as principles and implementation on the part of politicians, artists, and intermediary support providers. This publication also conveys a sense of the importance placed on documentary archives.)

Thus, even during the pandemic crisis, Germany has provided assistance not only at the federal government level. State and local governments with a thorough understanding of regional circumstances, and various actors in civil society who understand the realities of the creative/cultural sector, have applied knowhow gained through their usual up-close, in-person activities, and carried out urgently needed action in a pragmatic way. Additionally, numerous crowd-funding campaigns based on appeals from private foundations, influential artists and politicians have helped compensate for insufficiencies in government support and added depth to assistance efforts.

An “assistance/cooperation/self-help” emergency support system made up of a variety of participants. It was because of the decentralized cultural policy structure, including state governments with power that in normal times exceeds that of the German government, that the system’s multilayered structure demonstrated its efficacy. In a federal system, conflicts among the various participants are not uncommon in normal times; and it was extremely significant that, in order to provide emergency assistance, they temporarily put these conflicts aside to hold talks, build consensus and find solutions in a cooperative, reciprocal and complementary manner. In this way, various entities existing on multiple levels of a nationwide network acted in their respective roles and in cooperation, and united in support of a cultural/creative sector that showed society “solidarity” by suspending its own activities amid a state of emergency requiring containment of the virus.

> The outlook for Japan through the lens of Germany’s pandemic-related cultural policy (Part 2)

Related Article

- Introduction

- CASE01

U.S: Transformation caused by the pandemic, transformation ongoing under the pandemic

Kosuke Fujitaka (NY Art Beat co-founder) - CASE02

Art in the Face of COVID-19 – Australia

Julia Yonetani (Contemporary Japanese-Australian Artist Duo “Ken + Julia Yonetani”) - CASE03

Taiwan: The state of museums in Taiwan amid the COVID-19 pandemic

Huang Shan Shan (Director, Jut Art Museum) - CASE04

Hong Kong: What Opportunities Does COVID-19 Offer the Arts?

Mizuki Takahashi (HAT (Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile) Executive Director and Chief Curator) - CASE05

The Outlook for Japan through the lens of Germany’s pandemic-related cultural policy (Part 2)

Yuki Akino (Associate Professor, Dokkyo University) - CASE06

Reflections: Preparing fertile ground for culture beyond the COVID-19 pandemic (Part 1)

Shunya Yoshimi (Professor, Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies, The University of Tokyo) - CASE06

Reflections: Preparing fertile ground for culture beyond the COVID-19 pandemic (Part 2)

Shunya Yoshimi (Professor, Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies, The University of Tokyo)