Series: Arts, culture and expression in the age of coronavirus

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has brought major crisis and change to arts and culture on the ground.

In this series of pieces by individuals and experts active in different fields, we hear a variety of perspectives on the realities and challenges, as well as the future possibilities.

2020/10/09

For all the kani kamaboko (fake crabmeat) of the COVID-19 crisis:

The Association for Studies of Culture and Representation Symposium “Culture and Expression under the COVID-19 Crisis”

Professor, Faculty of Letters General Department of Humanities - Department of Film and Media Studies, Kansai University

Takeshi Kadobayashi

Series: Arts, culture and expression in the age of coronavirus

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has brought major crisis and change to arts and culture on the ground.

In this series of pieces by individuals and experts active in different fields, we hear a variety of perspectives on the realities and challenges, as well as the future possibilities.

As part of The Association for Studies of Culture and Representation’s online research forum 2020, a symposium entitled “Culture and Expression under the COVID-19 Crisis” was held on August 7, 2020. In a situation where forum attendees are unable to gather on a university campus and hold a normal convention due to COVID-19, the online research forum was itself planned as a way of keeping the Association’s research exchange activities going. For an association that widely researches thought, ideas and the arts, it was therefore natural to take the artistic and cultural situation under COVID-19 as its theme for the symposium. A detailed report on the symposium should be available on the Association’s online newsletter “REPRE” at a later date, but in this column I would like to set down my impressions and reflections as the person in charge of planning the symposium.

What comes to mind first in terms of the overall situation for arts and culture under COVID-19 is the predicament of cultural institutions such as theaters, movie theaters and museums that they are not able to open; or even if they do open, that they have no choice but to considerably restrict the conditions under which they open. Since February 26 when the government asked the public to exercise self-restraint in terms of attending events, most cultural institutions across the country have been forced to close temporarily. And although the situation has gradually been relaxed following the lifting on May 25 of a nationwide state of emergency, it seems that it will still be some time before things return to a state in which people can enjoy going to theater or exhibitions freely and without restrictions, in terms of both organizers’ social responsibility and the individual audience member/visitor’s psychology.

In response to these societal conditions, we have seen growth in crowdfunding and petitioning across diverse business sectors aimed at supporting cultural activity. Particularly high-profile is the merger in early May of three industry-specific movements launched between March and April – #SaveOurSpace (the music industry), SAVE the CINEMA (the movie industry) and the Emergency Financial Support Project in the theater world – to form #WeNeedCulture, which has been active on a variety of fronts including lobbying.

On the other hand, there has been a remarkable trend within many artistic genres for finding an online platform for expression. Theaters all over the world are streaming past performances and new productions online, and art museums and galleries worldwide are offering various forms of online viewing and virtual tours. In a sense, it has become possible for cultural facilities around the globe to be accessed from home without the limitations of physical distance, and there is no doubt that many people have been busily absorbing culture day and night through online video and images, prevented from leaving the house by emergency restrictions. We have also seen a variety of new forms of expression that take advantage of the characteristics of the online medium, including the one-time craze for “Zoom theater.”

So in other words, we can probably set out the state of affairs as follows: in a situation where creative activities cannot be conducted in places like theaters and art museums as actual physical spaces, social support is available on the one hand, and on the other a means of survival has been found in online space as an alternative platform for expression. One issue in this case is whether or not to regard creative expression in actual physical space as the real thing, and expression in online space as nothing more than a substitute and often merely an inferior copy. As mentioned by Masato Eguchi, one of the speakers at the symposium, in the opening message by theater director Satoshi Miyagi for the online event “World Theatre Festival on the Cloud” at Shizuoka Performing Arts Center (SPAC) (where Miyagi himself serves as General Artistic Director), Miyagi likened online theater to having kani kamaboko (fake crabmeat) when real crabmeat is unavailable. In other words, online theater (kani kamaboko) is a substitute for times when you can’t enjoy stage performances (crabmeat) at the theater; they are similar but different. But this metaphor raises some interesting points beyond merely indicating the relationship between an original and a copy. Maybe kani kamaboko will evolve as a unique taste, not just an imitation of crabmeat.

The first time I heard this excellent kani kamaboko metaphor was when Eguchi pointed it out on the day of the symposium. But it seems to me when I look back that this was the question that had intrigued me from the planning stage onwards of the “Culture and Expression under the COVID-19 Crisis” symposium. The predicament of venues not being able to open their doors is certainly alarming, and social support for them is absolutely necessary. And while the doors remain closed, it is a blessing for both artists and audiences to have an online forum for creative activities as an alternative. However, should the online form of expression be nothing more than an imitation incapable of being the real thing, the atmosphere would become really depressing. I ask myself whether it is out of the question to have the perspective to discover new possibilities for creative expression under COVID-19 and break away from the rigid system of delineation regarding real and lookalike, original and copy. If it is out of the question, this long-lasting COVID-19 crisis will be considered nothing more than a half-hearted, passive era in which originality was rejected. As for me, I would rather have a comprehensive taste of kani kamaboko that has evolved in a unique way precisely because of this era. I think the same thing could be pointed out with regard to theater performances and exhibitions under various restricted conditions, and not just with regard to forms of online expression.

Being first and foremost a media theory scholar, these ideas of mine may be attributable to the fact that I’ve always been interested in artistic expression that utilizes technology. In addition to this, my interest in monitoring artistic expression produced in times of crisis provided compelling motivation for planning the symposium. The reports given by each of the speakers at the symposium fully met my expectations. Performing arts researcher Masato Eguchi, who I have mentioned already, cited a variety of examples in his critical examination of how we should think about the live aspect of online theater. To be “live” fundamentally means the performers and the audience are present in the same place at the same time, something considered the ontological requirement for stage arts, but in today’s world of ubiquitous and diverse technology-channeled experiences, our idea of what constitutes live performance is no longer clear-cut (for example the oxymoron of “live recording”!) Not only that, in contemporary performance research the “live” aspect is not regarded as an essential requirement for stage arts; instead, the viewpoint has been put forward that “live” is a historically accidental terminology. That being so, we could even say that online theater, rather than being a clone of genuine theater, is a practice that shakes the foundations of theater’s existence by questioning what makes theater theater.

Tamako Akiyama, a scholar specializing in Chinese documentary film, reported on the situation for China’s independent filmmakers under the motif of “doors and walls.” According to Akiyama, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, unofficial (non-state-sanctioned) Chinese arts had only been allowed to operate in something like a state of self-isolation. Akiyama likens this situation to a traditional Chinese Siheyuan courtyard house. In other words, the authorities have only tolerated activities in a Siheyan-like environment, surrounded by walls on all sides, with only authorized persons being allowed to come through the door. In the 2015 documentary film by Wo Wang “A Filmless Festival”to which Akiyama refers, this unspoken agreement was broken at the 11th Beijing Independent Film Festival of 2014. The film depicts how the police used a ladder against the wall to enter the venue, and forced cancellation of the festival. In this way, independent Chinese filmmakers have been able to weather out the COVID-19 pandemic precisely because they have existed in a situation where they can only work in places that by their nature are isolated from the outside world, and because they don’t know when the safety of that place is going to be threatened. Akiyama showed us how Chinese filmmakers, both men and women, have been quick to find a platform for new forms of expression in the online environment, continuing their creative activities by interacting with the global network in a state of self-isolation.

Switching at high speed between a large number of open browser tabs, Brussels-based artist Yuki Okumura gave us a report on what he did and thought about during a period that in a sense amounted to a state of self-isolation under lockdown in Europe, a situation which has been far more severe than in Japan. Okumura, who combines his artistic activities with numerous contemporary art-related translation projects, working with people in the artworlds of Japan and North America from his base in Europe, said he felt more comfortable in an environment where every physical location is equidistantly linked through the Internet on the leveling plane of the computer screen. What especially left an impression on me from his report was the expression the “Three Kaku” (the Three Distances), which Okamura quoted from a tweet of his. His suggestion was that rather than the government-promoted “Three Mitsu,” a passive-sounding slogan turned catchphrase which urged people to avoid the “Three Mitsu” (the Three Cs in English) i.e. Mippei (closed spaces) Misshu (crowded places) and Missetsu (close-contact settings), it might be better to use the more proactive expression “Three Kaku,” encouraging people to practise Kakuri (quarantine), Kankaku (social-distancing) and Enkaku (remote work). This idea of viewing the situation under COVID-19 in an extremely positive light is even more revealing and significant when you read the following words quoted by Okumura from his tweet:

“The days under lockdown were comfortable for me because there is a universal reality (to my way of thinking) that says the world where each individual lives is an inward-looking “enclosure” and that there is an “inescapable distance” between individual lives, and maybe because this universal reality has been “implemented” in society in the form of Kakuri (quarantine), Kankaku (social-distancing) and Enkaku (remote work)” (from a tweet dated June 9, 2020).

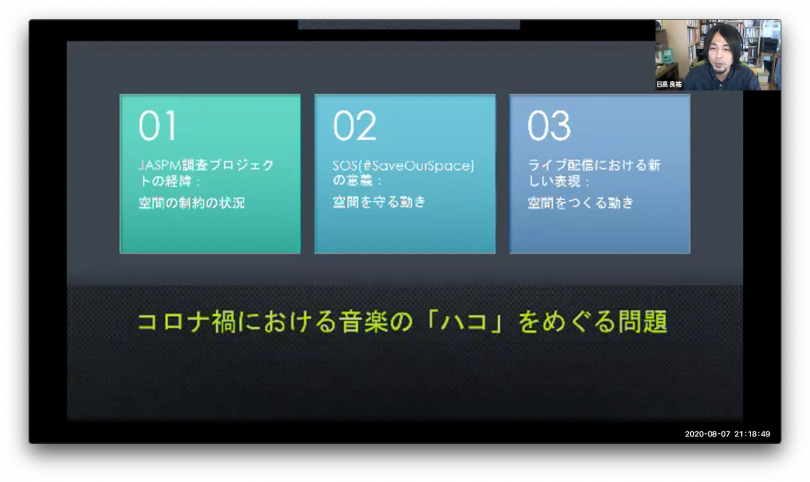

Lastly, we were given a report on the initiative “COVID-19 and the music industry: JASPM emergency investigation project 2020” by Ryosuke Hidaka, a researcher of popular music who is himself involved in the project. This project, started by JASPM (The Japanese Association for the Study of Popular Music) in early April 2020, is one of the speediest reactions to the COVID-19 epidemic by a Japanese humanities organization. Specific surveys were conducted through questionnaires and interviews with people involved in primarily small-sized music venue operations like live music clubs and nightclubs. What emerged from these surveys was that it isn’t just music venue operators and performers who are suffering under COVID-19; the pandemic’s effect extends to a huge range of jobs and culture supporting the live music industry (activities which musicologist and writer Christopher Small dubbed “musicking”), including sound and lighting technicians, vendors of merchandise, food and drink inside venues, and venue landlords. Hidaka points out that particularly since the music venue business structure is heavily dependent on freelance and part-time staff, the serious influence of the virus consequently extends to diverse players at the fringes of the music venue industry who form a sort of “ecosystem” that supports the venues. Hidaka also points out that the effects of COVID-19 are shaking the sense of community fostered by this “ecosystem.” On the other hand, the music industry is also making strides in terms of shifting to an online environment, and although a few venues are trying live streaming, major players such as Zaiko, PIA LIVE STREAM (PIA), and Streaming + (eplus) have apparently already entered the field and begun a battle for supremacy. No doubt one could say that these developments are also a part of “musicking,” but for my part they seem to be driving the further disadvantaging of small businesses, and accelerating a structure that will impoverish the industry at its periphery.

It is a difficult situation for sure. But when did this time of crisis begin exactly? That was the question thrown out by symposium discussant, sociologist Yoshitaka Mori. In fact, a situation like the power struggle between live music streaming platforms did not occur for the first time under COVID-19; rather, it would be more appropriate to view this as a trend that was underway beforehand and accelerated by the pandemic. And needless to say, a major factor in the worldwide scale of the pandemic itself lies in the accelerated movement of people and goods as a result of global capitalism rather than in the natural phenomenon of new pathogens emerging. In that sense we should view the predicament currently being experienced by spaces for creative expression as something that will continue in a different guise, and not go back to normal after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather than endure the time of crisis as something that will pass, I feel we should focus on the new forms of expression that emerge from it; and this is why it is will be even more essential to provide all possible support.

Related articles

Series: Arts, culture and expression in the age of coronavirus

- Tokyo – Coronavirus, Year One

Artist / Professor at Tama Art University’s Department of Sculpture

Tadasu Takamine - Creating for the stage under COVID-19

Director of NPO alfalfa/Art Manager

Kako Yamaguchi - The film industry under COVID-19

Tokyo FILMeX director/film producer

Shozo Ichiyama - Will you infect your co-performers?

Tokyo Festival General Director / General Artistic Director of SPAC (Shizuoka Performing Arts Center)

Satoshi Miyagi