Series: Arts, culture and expression in the age of coronavirus

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has brought major crisis and change to arts and culture on the ground.

In this series of pieces by individuals and experts active in different fields, we hear a variety of perspectives on the realities and challenges, as well as the future possibilities.

2021/03/29

Tokyo – Coronavirus, Year One

Artist / Professor at Tama Art University’s Department of Sculpture

Tadasu Takamine

Series: Arts, culture and expression in the age of coronavirus

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has brought major crisis and change to arts and culture on the ground.

In this series of pieces by individuals and experts active in different fields, we hear a variety of perspectives on the realities and challenges, as well as the future possibilities.

I’m an artist and an instructor at an art university. Incidentally, I’m also a husband and father. At the end of March last year I moved to Tokyo from Akita, and along with this major change in my living environment, I started teaching at a new university. In other words, I moved here just when the coronavirus was starting to spread in Japan. Since several changes happened at the same time, it’s hard to say how much was due solely to the coronavirus situation. In that period there had been fewer occasions to show my work, so my life as an artist wasn’t greatly affected. At the new university I had a better environment for creation, and spending a lot of time making things in the university workroom was more comfortable than it had been before. For these reasons, I’d like to write about my thoughts as a city resident and university instructor, rather than as an artist.

As a resident

My new home was in an apartment building near my workplace. When I was young, I never imagined that one day I’d live in a so-called “new town”—a planned housing development. I thought of these places as controlled settings where anything that threatens people’s safety and any irregular encounters are kept out. When I came to Tokyo and lived in a “new town” for the first time, that’s exactly how it was. The unexpected thing was that I felt it was more pleasant than any place I’d lived before. I actually surprised myself. Sidewalks stretching through the town, lots of trees along the road…and no electricity lines, so the Mediterranean-style rooftops stood out clearly in the sky. I didn’t feel that the planners who designed the town had any intention of standardizing people—on the contrary, I felt they’d made a serious effort to create a town that would be equally comfortable for each person. You don’t see disparities here. Everyone lives in the same type of building, wears the same type of clothes, shops at the same supermarket. Status is invisible. Occasionally you see a foreign person lining up at the register, holding an eco-bag like everyone else. There’s no noisy bustle. You don’t hear loud voices or music. Everyone lives here with the same sort of calm tension.

Mask wearing was already the norm when I came to live here, so I don’t know what it was like before. If the coronavirus situation caused any visible change in the town, I imagine it was simply the addition of masks. I have no doubt that, once the masks are gone, things will look just as they did before. There doesn’t seem to have been a major change in the townscape. Of course, there must be people who have lost their jobs. There might even be domestic violence, since people are staying home a lot more. But these problems within households don’t show on the outside.

When the worldwide lockdown began, there were stories in the news about opera singers living in apartment buildings in Italy who sang loudly from their balconies for their neighbors. Sound carries well from the apartment buildings here, too, so it would certainly travel a long way if opera singers sang from them. What happened in Italy could never happen here, though—I can’t even imagine it. In the early days of the pandemic, I thought that was a pity. It seemed to me that, when neighbors can’t visit one another freely, singing from the balcony to show one’s feelings was truly an act of kindness—like giving flowers to each person. But if you did something that dramatic here, it’s certain that, far from applauding, people would silently close their windows. It isn’t only here; I’m sure the same is true for Akita. In this country, people have been unconsciously keeping a distance from others since long before social distancing became standard. In this way, people gain comfort through restraint. If the comfort that people in Italy achieve through active community-building can be called “active comfort,” the comfort that people in Japan obtain by avoiding relationships might be called “passive comfort.” This being the case, I can’t think of any lifestyle habits here that need to be changed drastically because of the pandemic. This brings to mind what Singaporeans say in a self-deprecating way about their own country: “It’s true that having so many rules is annoying, but the country is stable economically, so life is fairly comfortable.” After Covid gets under control and things go back to normal, will Italian-style active comfort ever find its way to Japan, or will the world—Italy included—resign itself to passive comfort?

As a university instructor

Soon after taking up my post as head of the sculpture department, I faced a lot of difficulties as a result of the school’s closure due to Covid. Sculpture is a very physical field, so you might say there’s something fundamentally illogical about online sculpture lessons. I was making efforts to get in-person classes going as soon as possible, but in the three-month period from April to June, lessons were all online and we implemented various programs.

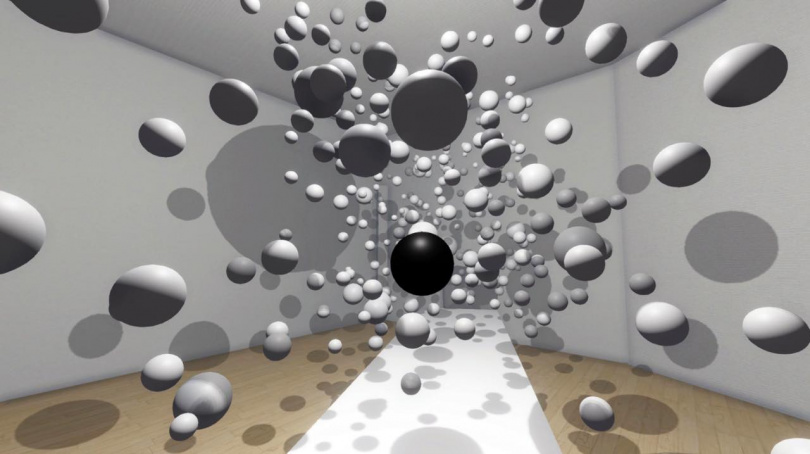

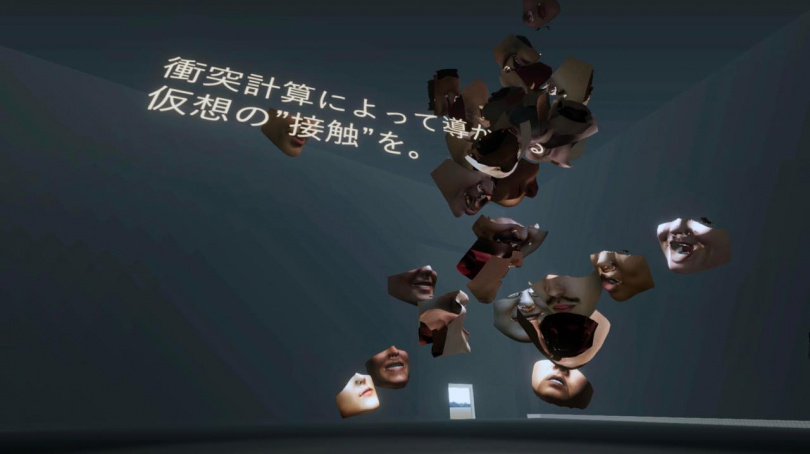

One well-received program was the “virtual sculpture exhibition.” With the multifaceted help of Akihiko Taniguchi of our university’s Department of Information Design, we put on a sculpture exhibition in a virtual space. While sculpture is normally constrained to a large extent by gravity, in a virtual context there are no physical limits, so it’s possible to make something a thousand times bigger, time is reversible, light can be placed anywhere or turned off, and nothing breaks or deteriorates. In other words, you can make works of art freed from all physical restrictions. Conversely, the project also clarified the types of constraints that are normally placed on sculpture. At the end, Mr. Taniguchi created spaces in which to place the works. With conventional exhibitions, works are usually created to suit the spaces. At best, the spaces can be selected. But in this exhibition, the spaces were created to suit the works. This was a real revelation to me. The program contained a lot of hidden suggestions about conditions for producing works of art, and turned out to be really stimulating.

From the “Tamabi Virtual Sculpture Exhibition”

From the “Tamabi Virtual Sculpture Exhibition”

From the “Tamabi Virtual Sculpture Exhibition”

From the “Tamabi Virtual Sculpture Exhibition”

From the “Tamabi Virtual Sculpture Exhibition”

From the “Tamabi Virtual Sculpture Exhibition”. You can download and browse the app from the website .

In the “Online Kobo” program, we sent project materials to students’ homes and provided online guidance. The “Lecture Ekiden” was a series of weekly one-hour self-introductory lectures by faculty members and assistants. Since the university allotted a special coronavirus response budget to each department, several other workshops were also incorporated into the program. On the whole these were quite well received. I was really gratified when students said, “The Sculpture Department’s response in the coronavirus situation was excellent.” Needless to say, this was thanks to cross-collaboration and cooperation among faculty members. Personal feelings aside, things could never have gone so well without the combined skills of the individual instructors.

Nevertheless, I do have some concerns about the future. One of them has to do with “touch.” Art relies to a huge extent on the sense of vision, so much so that the word “art” is used almost synonymously with “visual art.” While some recent works incorporate senses other than sight, these are generally positioned in an “others”-like context. The predominance of the visual sense shows no sign of wavering. “Vision” tends to turn into information and end up as “visual information.” The information is analyzed and processed, and the result becomes the value of the work. This communication sequence is entrusted to experts, and in the end the works’ flavor and texture don’t remain in the catalogue.

On the other hand, the sense of touch affects sensory input more than people imagine. The feeling of the water after washing one’s face, a blanket that retains warmth, wind hitting skin, ice crunched with the back teeth. It is known that people with visual impairment perceive these things in a three-dimensional way.

I once created a work with actors from Thailand and Japan. They couldn’t communicate well with language, and the thing that quickly closed the distance between them was a massage activity. Another time I gave a workshop where people closed their eyes and touched several other people’s palms, and I was astonished by the richness of their imaginations. In terms of the sense of touch, the experience of touching another person is unique and can’t be reduced to mere information. The body captures the feeling directly, before it turns into information. In this time of coronavirus, when direct physical contact is restricted, it isn’t enough to implement only educational programs that are weighted towards the visual. This is easy to grasp if you imagine the situation in which Helen Keller was taught language. (So what should be done? I can’t answer that. Right now I’m only saying it isn’t enough.)

Scene from a class in a laboratory, Department of Sculpture, Tama Art University

Scene from a class in a laboratory, Department of Sculpture, Tama Art University

Something else that concerns me is the question, “Where are the fully realized works of art?” Serious, real, original works in their unique and highest form. With the current Covid crisis, people are using expressions like “provisionally” and “for the time being” more frequently. And in most cases that’s the way things end up—provisionally decided. Original plans vanish in the mist. Works of art require instantaneous energy. There are times when you have to give form to an idea immediately, or the work will get away from you. When we’re young, for instance, we may have a good idea and set it aside, saying, “I can’t do that now,” only to lose sight of the idea’s landing point. With the coronavirus, I worry that we may wind up awash in the ruins of unrealized plans. Or else—and this also relates to what I just said about the sense of vision—we may start seeing screen images of artworks with the feeling that we’re seeing the real thing, and miss out on the chance to experience the works in their complete state. Seeing the real thing means experiencing the work totally, including but not limited to the visual aspect. We need to take care not to misunderstand this point and end up setting lower goals for our own creations. Since we have fewer opportunities in this time of coronavirus to experience actual works of art, I feel that we need to alert students to this issue.

These are some random thoughts from the perspective of a city dweller and university instructor. In either case, the feelings I’ve experienced are trivial compared to those of someone like a restaurant manager. At our university, it was announced in the general staff meeting of April 2020 that “This isn’t a situation that will cause the university to suddenly close down.” Those were very encouraging words! Though the faculty members didn’t actually shout “Hurray!” I’m sure they were all quite relieved. Of course, everyone worries that some universities might eventually have to close their doors if the situation goes on much longer.

I think teachers, and not only those at universities, feel that they’re not simply teaching the students sitting in front of them. At least that’s true in my case. No matter what school I’m a part of, I’m always thinking that I’m connecting with the local area, the country and the world, and hoping my words and actions will someday, somewhere be of use to society. I’m happy if a student with whom I’ve made a connection becomes active somewhere in the wider world. Leaving aside the idea that I’d have problems if my workplace closed down, or the question of who has suffered the worst difficulties, right now I’m just thinking hard about what I can actually do. The following is from the message I wrote to the newly enrolled students of the 2020 school year.

This will be an irregular year, but isn’t it especially in times like these that new forms of expression emerge? This will surely happen at the same time throughout the world. Considering that this could also be a period of great conceptual transformation in the field of sculpture, I’m already looking forward to the time when you all graduate four years from now. Congratulations on your enrollment!

Related articles

Series: Arts, culture and expression in the age of coronavirus

- Creating for the stage under COVID-19

Director of NPO alfalfa/Art Manager

Kako Yamaguchi - The film industry under COVID-19

Tokyo FILMeX director/film producer

Shozo Ichiyama - For all the kani kamaboko (fake crabmeat) of the COVID-19 crisis:

The Association for Studies of Culture and Representation Symposium “Culture and Expresssion under the COVID-19 Crisis”

Professor, Faculty of Letters General Department of Humanities – Department of Film and Media Studies, Kansai University

Takeshi Kadobayashi - Will you infect your co-performers?

Tokyo Festival General Director / General Artistic Director of SPAC (Shizuoka Performing Arts Center)

Satoshi Miyagi